This is the second part of the blog post series about The Odyssey of Stark and Melody and more specifically, about the development of a prototype of the native compiler for the Stark language developed during last year.

Overview

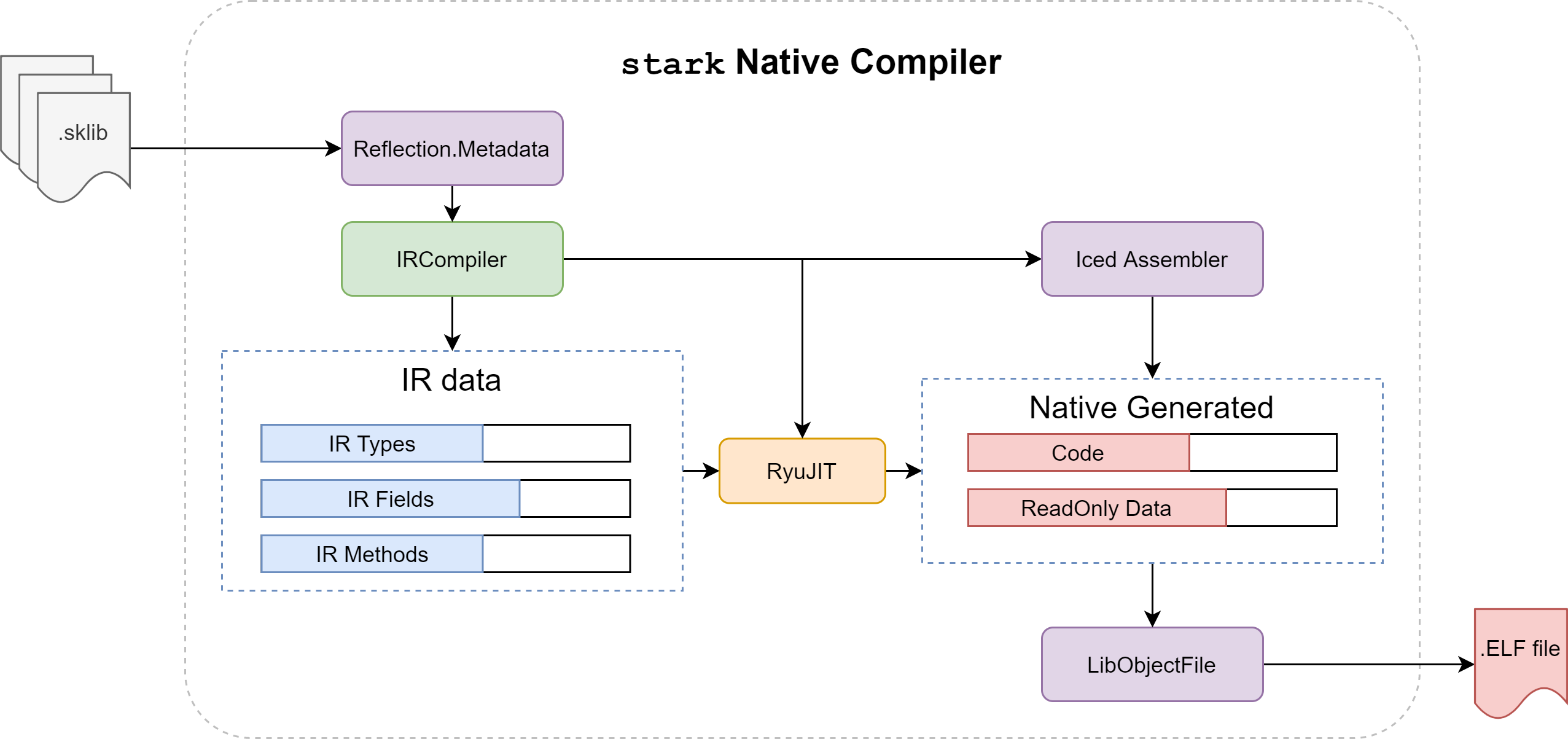

As we saw previously about the front-end compiler, Stark is a language meant to generate native executable code at build time (AOT compiler). From a set of Stark sklib pre-compiled libraries, we want to generate this native code.

After the Raspberry Pi4 experiment, I originally thought that I would reuse large parts of the CoreRT compiler and its runtime (the experimental AOT .NET compiler) in order to speedup the development of this prototype. But while digging more into the syntax of the language by developing the core library with the language itself, I realized that CoreRT would not be a good fit for the following reasons:

- The compiler doesn't fit into the data oriented approach I was looking for. Lots of managed objects are allocated and used around which are a source of inefficiency.

- The compiler is plugged into RyuJIT by implementing the entire callback interface (170+ methods) in C#

- Whenever RyuJIT is updated, you need to manually update a ThunkInput.txt text file as well as manually update new enum items...etc (See for example this PR to update RyuJIT)

- The fine-grained interface can be very chatty, requiring lots of native (RyuJIT) to managed transition to compile a single method.

- The compiler requires also to compile a LLVM library - the Object Writer - (16Mb+) in order to generate COFF/DWARF/MACHO object files.

- The compilation requires various low-level CPU dependent ASM files to be linked with.

- Many offsets need to be shared and maintained with the compiler/runtime in order to work correctly.

- The .NET Runtime in CoreRT is relying on some existing C/C++ runtime (e.g GC) while Stark will be entirely implemented in Stark.

- Many challenging parts in CoreRT will be implemented very differently in Stark:

- Interface calls in Stark are using fat-pointer.

- Delegates are not managed object in Stark but value types, either a direct function pointers (for static functions) or fat pointers for closure functions (e.g instance method of an object).

- Virtual methods with generics are not allowed in Stark.

- Static/Const data in Stark are entirely computed at compile time and baked into a readonly data section. This include loading string literals for example, which is a nop in Stark as there is no heap allocation involved for string literals in Stark.

- Generics would be handled up-front by the native compiler, allowing more opportunities/optimizations or different strategies for native code sharing, RyuJIT would not see any generics at all.

- Literal generics would be part of these optimizations.

For these reasons, I decided that the architecture of the native compiler would be significantly different to justify to not rely on CoreRT. Though, in order to keep the development practical, it would still rely on RyuJIT for generating native code but it would keep it as an implementation "detail", as it is done similarly in CoreRT. Other reasons for using RyuJIT:

- RyuJIT is a compiler aware of managed objects references (for precise stack root walking).

- It provides correct reporting of stack frame walking and managed objects on the stack.

- RyuJIT is being improved constantly.

- RyuJIT provides good codegen balance between throughput and optimizations.

Let's see how the native compiler of Stark was designed and developed.

Architecture

The key requirements of the native compiler are:

- Design the compiler up-front using data-oriented structures to improve its efficiency.

- Take into account early in its design a server/incremental mode to allow to cache assemblies, detect modifications...etc.

- Rely on RyuJIT as a base - for simple - IL compiler to native code:

- Move some of its prerogatives to the higher level (e.g generics, some code elision/inline decisions...).

- Keep modifications required for RyuJIT to its bare minimum.

- Use an intermediate IR to perform higher level transformations before going back to RyuJIT

- So the transform process for RyuJIT would be: IL (from sklib) => IR + transforms => Simple Il (for RyuJIT)

- Allow this IR to be used later by a different IR to native code path (e.g custom IR to native compiler, LLVM...)

- Make every parts of the compiler streamlined, integrated and fine-grained control. The compiler should be able to perform on its own without relying on external tools:

- Generate low-level assembler parts.

- Perform linking and layout of the generated executable.

- Write debug information.

Unlike a regular C/C++ compiler, the process of compilation can be more focused: we know for example the entry-point of an executable in an sklib and in that case we can transitively collect exactly what we will need to transform to native code. sklib libraries should be seen as pre-compiled headers stored in a compressed data-layout format.

When processing these methods, we are going to collect lots of data that we need to un-compress and organize in memory to allow to process them more efficiently later.

Data Oriented IR

What does it mean for a compiler to be data oriented? It is actually quite challenging because a compiler manipulates trees of instructions and these trees can be transformed, new nodes can be created and this often doesn't translate back to sequential memory access (after a few transforms), unless we compact/reorder our data after a few transforms based on some fragmentation levels and on the remaining amount of transforms or analysis that still need to proceed. This sequential memory access problem is mostly for instructions. Other type system related metadata are less affected and can be layout in memory relatively efficiently.

But there are other related aspects of being data oriented:

- Adapt the data to a particular process, usually the most common/time consuming process.

- Take the word "oriented" in data oriented as oriented to a particular process need. Different process can require different optimal data layout. The goal is not to find a general purpose data layout valid in all kind of situations.

- If we have a chain of processes where some processes are going through the data in a completely orthogonal manner, decide whether we need to build a more suitable data layout view (e.g re-layout-copy vs index indirection).

- Craft the data to present a maximum entropy/locality of information at one place.

- Make allocation and de-allocation fast.

- Avoid unnecessary copy of data.

When processing IL, we have many different connected data:

- Methods

- Signatures

- Parameters

- Local variables

- Basic blocks

- Instructions

- Arguments

- Users (instruction dependencies)

- Arguments

- Instructions

- Signatures

- Types

- Fields

- Generic types

Arena Allocator

Because we are collecting methods on our way, we don't know exactly how much data we will need to finally transform to native code.

If we were using a naive approach, we would use something like this:

// Assuming that IRMethod is a struct

var methods = new List<IRMethod>();

...

while (methodsToVisit.Count > 0) {

var irMethod = ... // Build IRMethod

// Make a copy of IRMethod to the array

// but also potentially, resize the underlying array

// and copy all previous methods to the new array

methods.Add(irMethod);

}

To our principles defined earlier, even if IRMethod is a struct, this approach is not enough data oriented friendly: We are still making lots of copy of data.

We could decide to pre-allocate List<IRMethod> with an original capacity, but this is not great to allocate and consume potentially lots of memory that in the end would not be used at all.

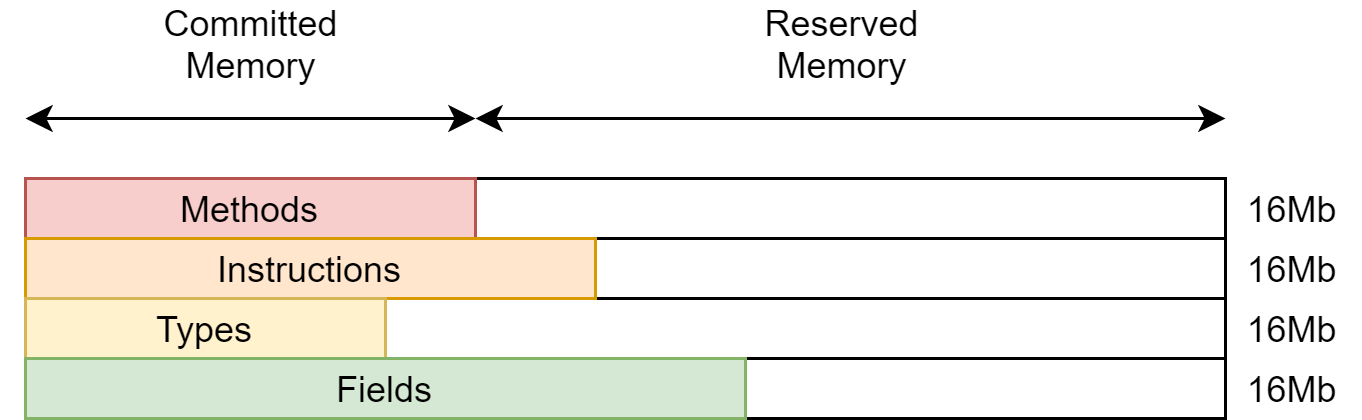

Instead for the Stark native compiler, a dedicated virtual memory arena allocator is used for each kind of data to allocate:

Each kind of data has its own continuous block committed (actually used) and reserved (maybe used later) virtual memory. Whenever we have to add some data to a block, we just need to transform a reserved memory page into a committed memory page while keeping the same initial base pointer for the block.

Each block of memory is storing a single kind of data so that we can index them (instead of offset-ing).

Finally, this arena allocator is very easy to collect or reuse, no need for a GC to visit every single reference to realize that it can free large block of memory. Once we are done compiling a graph of methods, the same areana allocator can be reused for subsequent requests. Resetting the allocator just requires to reset the start pointer to zero. That can be massively effective when using this approach in a shared compiler server.

Index-based references

Because the memory used to store these data is unmanaged, we can't store any managed references in them (we could use GCHandle but that's not the point). Moreover, each kind of data might references other kinds (e.g a method has basic blocks, each basic blocks has instructions...).

As the memory blocks are contiguous and are guaranteed to not be re-allocated, we could use pointers to connect them. But again, pointers in that case are actually not data oriented friendly. On a 64 bit arch, their footprint adds-up quickly, specially when you have lots of references. For a simple, case like an IRFieldDesc structure:

struct IRFieldDesc

{

IRFieldFlags Flags;

IRTypeHandle DeclaringType;

IRTypeHandle Type;

uint64_t AddressOrOffset; // address if flags is static, offset otherwise

IRUTF8StringZero Name;

};

Using a pointer for IRTypeHandle would increase the size of this struct by 25%, from 32 bytes to 40 bytes. It could be seen as acceptable, but it is one of the best-case struct in the IR model, while there are other cases that are much worse (1.5x to 2x bigger).

Instead, we are using 32-bit indices to address and connect data. This should give plenty enough room to index our data (4 billions of entries per kind).

Reducing size for data oriented data is particularly important to improve cache utilization - which is usually the bottleneck of most modern workload these days.

When using indices, we are usually always reserving the index 0 as a null reference (not used). Another interesting side effect of using indices is that you can clone data without having to patch the indices referencing these data.

IL to IR

The IL in a sklib is stored in a compressed format, well suited for a compact and efficient storage for IO, but absolutely not efficient for manipulating it. For example, some integers/indices in IL metadata can be encoded using a variable-length encoding scheme. The stream of IL instructions of a method has to be decoded from the start of the method in order to access a certain instruction.

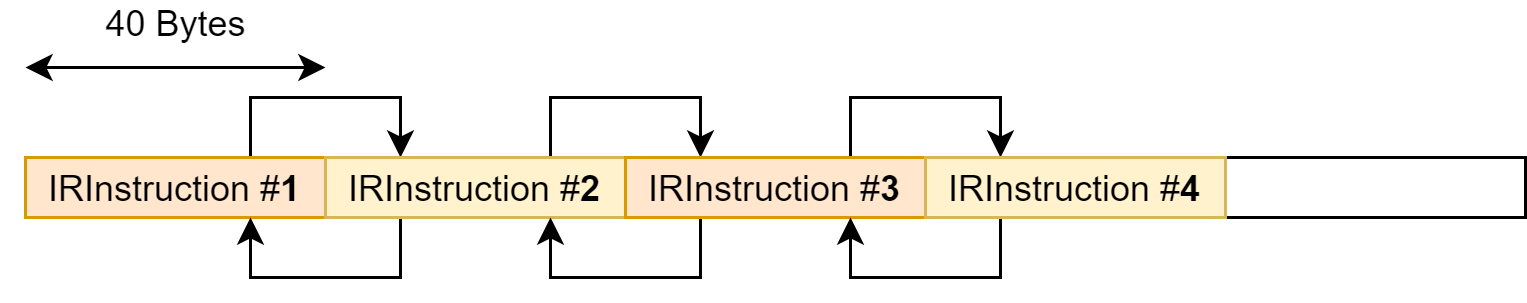

In Stark, we transform IL instructions along all the associated data (methods, types, fields...) to an IR representation that is more suited for traversing and transforming. The stream of IR instruction is encoded as a continuous linked list of fixed-size instructions as it is important that the underlying container supports addition/insertion/removal of instructions without having to copy or shift a large amount of data.

For instance, a single IR instruction in Stark is occupying around 40 bytes, while most instructions in the IL can occupy as little as 1 byte. Why there is such a huge difference with the IR?

The reason is that we need to manipulate efficiently these IR instructions at compile time, detect what is the final type of the operation, find users of a particular instruction (so that it can be replaced easily)... Also the IL is encoded as a stack of instructions (push and pop) which requires to process the instructions to know where we are, while the IR is register based, so an index of an instruction is its register/reference:

For example, the following IL:

// IL

ldarg.0

ldarg.1

add

Would be translated to the following (simplified) IR:

// IR

1 = ldarg.0

Previous: 0

Next: 2

Type: 1 (int)

Users: [3(0)] // Used by instruction 3 argument 0

2 = ldarg.1

Previous: 1

Next: 3

Type: 1 (int)

Users: [3(1)] // Used by instruction 3 argument 1

3 = add(1, 2) // reference instruction 1 & 2

Previous: 2

Type: 1 (int)

Next: 0

In order to decode the IL, we are using our own StarkPlatform.Reflection.Metadata/SRM which is a fork of System.Reflection.Metadata. As explained in the previous blog post, a fork of this library was required to make breaking changes on the IL and add new features.

SRM is a very well designed data-oriented library, suited to decode efficiently a sklib without having to expand or IL-uncompress the library into memory. It just requires to load (or even better - memory map a file) into memory and the library is working directly on the buffer without having to transform it.

Zero-copy UTF8 strings

Stark is using from the start UTF8 strings, for all metadata inside the sklib, for both strings used for metadata namespace/method/type names as well as for user literal strings. This is one of the breaking change made to the IL.

But SRM library was also slightly modified to more efficiently support these strings without requiring a managed allocation (unlike the original SRM). It means that whenever you need to access a string defined in an assembly (and you can have lots of strings in an assembly!), you can get a reference to it through a small wrapper struct which contains just a pointer to the array of bytes and a length. It provides a zero-cost abstraction when using strings which is very valuable in our data-oriented compiler.

Whenever we need to concatenate strings (e.g to build a full type name for example with generic arguments), we allocate new strings as part of one bucket in our arena allocator and we are able to create/copy/contact strings if needed and get a reference from there.

RyuJIT integration

RyuJIT is the JIT compiler used by .NET Runtime to compile methods on the fly. Its ICorJitCompiler interface is lightweight as it is completely decoupled from the IICorJitInfo interface providing actual metadata required for JIT to compile a method:

// Initialize the JIT with a Host callback providing global information to the JIT

extern "C" void __stdcall jitStartup(ICorJitHost* host);

// Get a pointer to the JIT Interface

extern "C" ICorJitCompiler* __stdcall getJit();

// The JIT interface to interact with

class ICorJitCompiler

{

public:

// compileMethod is the main routine to ask the JIT Compiler to create native code for a method. The

// method to be compiled is passed in the 'info' parameter, and the code:ICorJitInfo is used to allow the

// JIT to resolve tokens, and make any other callbacks needed to create the code. nativeEntry, and

// nativeSizeOfCode are just for convenience because the JIT asks the EE for the memory to emit code into

// (see code:ICorJitInfo.allocMem), so really the EE already knows where the method starts and how big

// it is (in fact, it could be in more than one chunk).

//

// * In the 32 bit jit this is implemented by code:CILJit.compileMethod

// * For the 64 bit jit this is implemented by code:PreJit.compileMethod

//

// Note: Obfuscators that are hacking the JIT depend on this method having __stdcall calling convention

virtual CorJitResult __stdcall compileMethod (

ICorJitInfo *comp, /* IN */

struct CORINFO_METHOD_INFO *info, /* IN */

unsigned /* code:CorJitFlag */ flags, /* IN */

BYTE **nativeEntry, /* OUT */

ULONG *nativeSizeOfCode /* OUT */

) = 0;

// ... a few other methods

}

Inspired by the design of CoreRT, I originally thought that I would implement the whole ICorJitInfo interface in C# by passing a custom virtual table to RyuJIT. Unlike CoreRT, I wanted to automate entirely the maintenance of this virtual table by generating it from source code instead.

So I started to develop the library CppAst (released almost one year ago!), a simple wrapper around libclang that provides an easy way to navigate C/C++ headers.

From that, I developed another library CppAst.CodeGen to generate a C# PInvoke layer from C/C++ header files. CppAst.CodeGen was heavily inspired by the work I did on SharpDX but was simplified and made more decoupled. It is not as rich as what was done in SharpDX, but it is good enough to handle most C/C++ header files. I even started to develop the wrapper GitLib.NET around libgit2 as a playground for CppAst.CodeGen. You can have a look at the generated files for this project. But I didn't continue much further GitLib.NET (I was already off-track for the Stark native compiler!) even If I believe that it could have been a much faster/slim/efficient interface around libgit2 compare to the existing LibGit2Sharp.

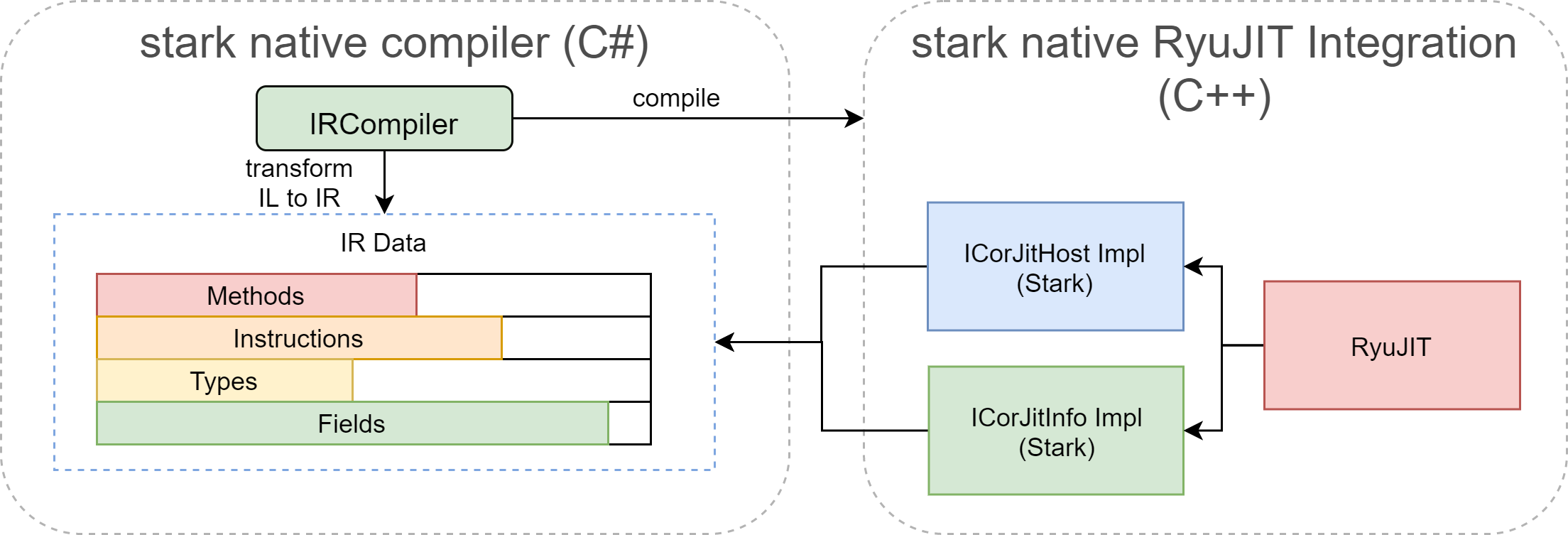

Anyway, after this code interlude (and we will see that there are others coming!) when I started much later in September to actually develop the Stark native compiler, I realized that instead of implementing entirely the ICorJitInfo interface in C#, I would implement it in C++ with only a pointer to the generated IR datas:

So, Was CppAst in the end developed for nothing? Actually not! As I had to make an integration with RyuJIT by implementing the entire interface in C++, I decided to model the IR in C as well. That was much easier to integrate it directly with RyuJIT, but with CppAst.CodeGen I could easily generate all the C# structs from this simple and straightforward API. It means that the interface between the Stark C# native compiler and RyuJIT integration was mostly data-oriented, with a single method to call RyuJIT:

// Initialize Stark/RyuJIT

STARK_NCL_EXPORT_API void StarkNclInitialize();

// Compile the specified IRMethod with the specified IRContext.

STARK_NCL_EXPORT_API void StarkNclCompile(const IRContextDesc* context,

IRMethodHandle methodHandle,

uint8_t** nativeCode,

uint32_t* nativeCodeSize);

In Stark, the IRContextDesc serves similar purpose than the ICorJitInfo, but it is exposing only data. The implementation of ICorJitInfo lives just behind this StarkNclCompile method but is very easy to develop as it is mainly extracting data from our IR and return them in the different implementation methods of ICorJitInfo.

For example, implementing the method ICorJitInfo::getClassNumInstanceFields is simply a matter of indexing in the IRClassDesc table:

unsigned CorInfoWrapper::getClassNumInstanceFields(CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE cls)

{

const auto type_handle = get_stark_ncl_type_handle(cls);

assert(type_handle.is_class_like());

const auto& type_desc = get_class_desc(type_handle);

return type_desc.InstanceFieldCount;

}

So we can better understand now how different is the integration of RyuJIT in Stark compare to CoreRT:

- In CoreRT, the compilation process transform IL to a representation using managed objects (the type system...etc.). Then RyuJIT is called with a callback interface

ICorJitInfoimplemented in C# that will access these managed objects to return the requested data to RyuJIT. Compiling a method requires lots of round-trip/native-to-managed transition in order to extract these data. The access to the data can be jumping around in memory - because there is no guarantee that these managed objects are all well co-located in memory, moreover, there are many managed allocations going around with more GC happening. - In Stark, the compilation process transform the IL to a data-oriented IR representation - on which we can operate more transforms before going to RyuJIT. Then RyuJIT is called only once with a pointer to these data and is able to to extract all the required information to compile a method. No other managed transitions are happening during this process, resulting in a much leaner and efficient integration with RyuJIT. The GC is barely involved, as the Stark compiler is data-oriented.

As this Stark RyuJIT C++ integration is actually another flavor of RyuJIT (e.g it creates a native DLL called stark-ncl-clrjit-x64.dll), I made a PR to dotnet/runtime to simplify the creation of my own C++ RyuJIT DLL outside of the CoreCLR repository.

This way of working with RyuJIT payed off as well later when I transitioned from the old CoreCLR repository to the new dotnet/runtime. In the meantime, the interface of ICorJitInfo changed a bit, some enums were removed, some methods were changed... but it took me just a few minutes to upgrade the Stark RyuJIT integration layer to this new version. I didn't have to touch at all the IR data during this process.

Generics and Inlining

Handling generics efficiently is an important challenge for reducing compilation time and avoid code-size explosion. But It is also often critical to generate efficient code for a particular generic case.

RyuJIT has been (re)using an effective rule since the beginning of generics in .NET Framework 2.0:

- Generated code for generics with reference types is shared (e.g

List<object>) - Generated code for generics with value types is specialized (e.g

List<int>) - A mix of both (e.g

SpecialList<object, int>)

Matt Warren wrote a great article about "How generics were added to .NET" and the original paper Design and Implementation of Generics for the .NET Common Language Runtime gives plenty of details about the implementation (part 4), so I won't give more insights here about the rationale but highlight some of the differences.

It has proven over the years to be a sensible rule overall:

- For value types, you often don't have much choice. If you don't specialize, you would have to go through quite some indirections to make the code shared (e.g query the size of an element type in an array everytime you want to access an element and index dynamically based on this sizeof).

- For reference types, it also makes sense, as a reference type is occupying the same space (a pointer size) and access to them can be gated through interface calls which can be shared.

I didn't change drastically these rules for Stark, but the implementation details are still different. Because we can have generic const literals (e.g FixedArray<int, 5>) it would require to change RyuJIT in order to support this new scenario. I would like to avoid as much as possible modifications to RyuJIT as it would complicate merging and future maintenance. So instead, generics are expanded at IR build time. This should also give more opportunities in the future to decide which generics should be shared or specialized. Typically, I would like to share structs which have the same layout of fields, it was mentioned in the original paper (Section 4.1 Specializing and Sharing: "That leaves user-defined struct types, which are compatible if their layout is the same with respect to garbage collection i.e. they share the same pattern of traced pointers") but I don't think that this is something currently implemented in RyuJIT (thought It might have changed recently!).

So in the end, RyuJIT is receiving only plain generic-less methods and structs to compile. This will also simplify later potential integrations with other native compilers (e.g LLVM).

Inlining can also erase the distinction between shared vs specialized because if the method being called is a candidate for inlining, it will be inlined whether it is specialized or shared, and thus, make the inlining actually specialized. You can see this in action with List<string>.Add(...) and List<object>.Add(...) on this example on sharplab.io.

It will be possible also to control the inlining at the IR level in order to cover some LTO scenarios that RyuJIT alone cannot make a decision about (e.g single method use).

Layout of Code

In a traditional C/C++ workflow, a compiler will roughly compile code and generate an object file per cpp file. Then a linker will glue these object files together to form a final executable. But if you think about it, it is actually far from being optimal in terms of locality and cache-coherency: Functions that are being used in a method call graph could potentially jump between several different locations/object files. This is what LTO (Link Time Optimizations) of some of these compilers are also taking this into account otherwise you can use solutions like BOLT to optimize the layout of your code.

In Stark - but I believe also in CoreRT, the layout of the code is following the method call graph, which result in a more optimal layout of the code straight from the beginning of the codegen. Though, the layout of code based solely on the method call graph is not necessarily the most optimal. You can come up with an even more optimal layout by using a PGO approach (Profile Guided Optimizations) where you run your code with instrumentation for which we can reuse the results to feedback the compiler with additional layout hints. Note that profile guided optimizations are also used for better inline decisions.

Layout of Data

Similarly, the layout of the data is actually impacted by the method call graph. In Stark, this is something even more important, because all static data are constant data that will stay in a readonly section of the executable.

Unlike in .NET/CoreCLR (and CoreRT, even if it can optimize certain scenarios), all (static) const objects are not allocated on the heap but will stay in the readonly section without generating any allocations.

For instance, if you take the instruction ldstr in IL ldstr "This is another string", in a .NET Runtime, this requires usually to allocate a string on the heap, copy the string content from its metadata assembly to the heap, store a dictionary to associate this original metadata string with its heap representation (this is called internalize). It is such a costly process that RyuJIT is even deciding to not inline a method whenever there is a ldstr somewhere in your method and another reason why you will see plenty of places in the .NET runtime where a throw new ArgumentXXXException("This is an awful string to load") will be moved to a separate method (see for example List<T>). (Edit: As suggested by a careful reader on Twitter - Hey Lucas! ;) - That was based on an old discussion but it seems to inline fine now with RyuJIT!).

Let see how this is handled for loading a string in Stark:

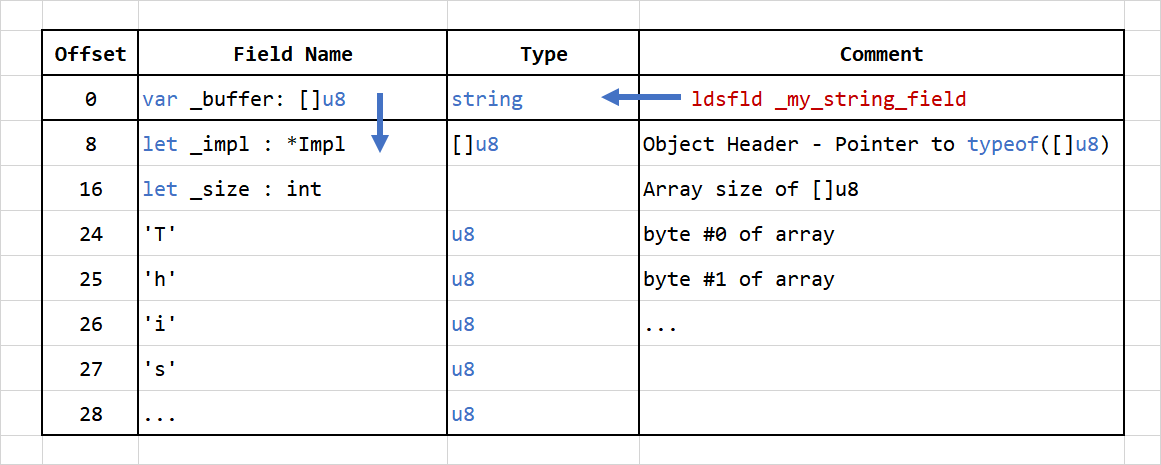

First, we convert ldstr "This is another string" at IR level into loading a static field value ldsfld _my_string_field. A string in Stark is a value type which contains a managed array of u8:

public struct String implements IArray<u8> {

private let _buffer : []u8

// ...

}

An array is a special type which contains first a length followed immediately by the elements:

public abstract class Array implements ISizeable

{

private let _size : int

// ...

}

public class Array<T> extends Array implements IArray<T> {

// First element of T (but this is handled by the native compiler)

}

but Array also inherits from Object:

public virtual class Object {

private unsafe let _type : Type

// ...

}

where Type is simply a wrapper around a pointer to simple runtime representation:

public immutable struct Type {

private unsafe let _impl : *Impl

// ...

}

Then the string is actually layout in the data section like this:

- Offset 0: is the address where

_my_string_fieldis located which is a structstring.- This entry contains an address to the internal

_buffer []u8.

- This entry contains an address to the internal

- Then the following entry is the actual layout of the object

[]u8- Offset 8: With a pointer to the type of

[]u8becauseArray<T>inherits fromArraywhich inherits fromobject. - Offset 16: The field

let _size : intis coming fromArray. - Offset 24 and followings: The string

u8elements data coming fromArray<T>.

- Offset 8: With a pointer to the type of

The metadata for Type are stored in a different location, and are all grouped together in a continuous block of memory.

Having data streamed along the way of discovering code allow to colocate data where they are used. It doesn't give a strict optimal solution (again requiring PGO to make it effective) but it should be on average much better, specially when a method access a few constant objects that it is only using, the compiler will make a guarantee that these data are layout in memory in consecutive cache lines, which can be very effective!

A careful reader could see that our object doesn't contain a GC Header. This is yet to be confirmed with the design of the memory manager, but I don't plan to have a GC header for managed objects. In .NET this is called ObjHeader (see syncblk.h) which contains bits required by the GC as well as a potential pointer to a shadow object runtime called the SyncBlock. When you do a lock(object) it will create and access this shadow object at runtime or same if you start to call the default Object.GetHashCode(). This GC header is unfortunately an - awful - story/legacy coming from Java which is bringing lots of unnecessary runtime burden to our object (a pointer size + a potential shadow runtime object). As a breaking change and to improve runtime efficiency, we can completely remove that implementation details in Stark!

Special functions

The native compiler in Stark allows to replace any external methods with a custom implementation. For example the following debug_output_char method:

@ExternImport("kernel_debug_output_char")

private static extern func debug_output_char(c: u32)

Can be redirected at compile time to an implementation that requires access to a special CPU instruction syscall which is unavailable via RyuJIT. Here is an example by redirecting this method to a Linux kernel method:

// Implementation of extern import "kernel_debug_output_char"

private void PatchLinuxKernelWriteMethod(ref IRMethodDesc methodDesc)

{

var c = new Assembler(64);

// https://blog.rchapman.org/posts/Linux_System_Call_Table_for_x86_64/

//

// void debug_output_char(int c) {

// sys_write(1, &c, 1);

// }

//

// 57 push rdi

// B801000000 mov eax,1

// BF01000000 mov edi,1

// 488D3424 lea rsi,[rsp]

// BA01000000 mov edx,1

// 0F05 syscall

// 4881C408000000 add rsp,8

// C3 ret

c.push(rdi);

c.mov(eax, 1);

c.mov(edi, 1);

c.lea(rsi, __[rsp]);

c.mov(edx, 1);

c.syscall();

c.add(rsp, 8);

c.ret();

AssembleMethod(c, ref methodDesc);

}

Most of the work was actually spent at developing an assembler for the project Iced that I happily pushed through a massive PR after several evenings of coding!

As we are going to need to access a seL4 micro-kernel while building our Stark-based micro-operating-system we will require several of these methods to interact efficiently with seL4.

Having a tight integration of the Stark native compiler with an integrated assembler allows to easily generate dedicated assembler code that can be dependent on other input data available at compile time (e.g constants, offsets, generation of variants of assembler code...etc.). It is also saving the time of a linker, which would be actually more costly, as the total time to read of the object file from disk, decode the DWARF section, copy the data to a new place in the final executable...etc. are requiring a lot more CPU cycles than to encode these instructions directly (Iced is also the most marvelous and fastest assembler I know about!).

Change to RyuJIT

The prototype was around generating code for a simple HelloWorld program using the following function:

module program {

/// ConsoleOut is a capability based object

/// using dependency injection known at

/// compile time (no dynamic resolution)

public static func main(cout: ConsoleOut) {

cout.printfn("Hello World!")

}

}

public partial module console_apps {

public struct ConsoleOut {

public func printfn(text: string) {

for c in text {

debug_output_char(c)

}

debug_output_char('\n')

}

@ExternImport("kernel_debug_output_char")

private static extern func debug_output_char(c: u32)

}

}

One important change that was made to Stark is that all arrays are using a native integer (int in Stark, which is 8 bytes for a 64 bit CPU arch) for their size.

I wanted to propagate this change also to RyuJIT to allow the compiler to perform proper IndexOutOfRangeException removal, so I took the side-time to also make these changes to RyuJIT. The changes are relatively small and I hope to be able to maintain them easily while merging back dotnet/runtime. But as for Roslyn, it is never easy to make a change to a repository you are not an expert in without having a review from someone more knowledgeable!

Generate an executable

In order to run an executable on an Operating System, you need to have a proper file format of this executable, how to layout code and data in memory...etc. For Stark, I decided to adopt the ELF file format for which you can find plenty of tools to manipulate them (at least on Linux and MacOSX).

As per our requirements, I wanted also this integration to be streamlined so I decided to develop a whole library for manipulating object files from C#/.NET called LibObjectFile.

This library helps to create easily ELF executable with whatever section/segments requirements we need for our case.

Because I wanted also the executable to be debuggable via qemu, I have also added support for DWARF debugging information. The DWARF specifications are huge and splitted between multiple versions of the specs, so the development of DWARF into LibObjectFile took me several weeks of work.

A Stark executable for the Melody OS is currently composed of 3 segments/sections:

- Code section

- Read-only data section

- BSS section (only relevant for the boot core server - to have an initial heap/stack available)

Symbols Relocations

Another challenge when linking code is that you need to relocate all the code and data (symbols) to a different final target memory location.

For code, whenever RyuJIT is emitting a relocatable code - accessing for example a data - it will emit a relocation entry which will perform a callback to our compiler (tip: one case where RyuJIT is calling back our compiler here). For most assembler code, relocation entries are relative 32 bit offsets to the end of the instruction using this data:

mov rcx, [rip + offset _my_string_field] // load []u8 data

Translates to the following instruction, where we can see the relocation entry of _my_string_field:

// mov rcx, [rip + offset _my_string_field] // load []u8 data

0x48 0x8b 0x0d 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

"Relocation entry"

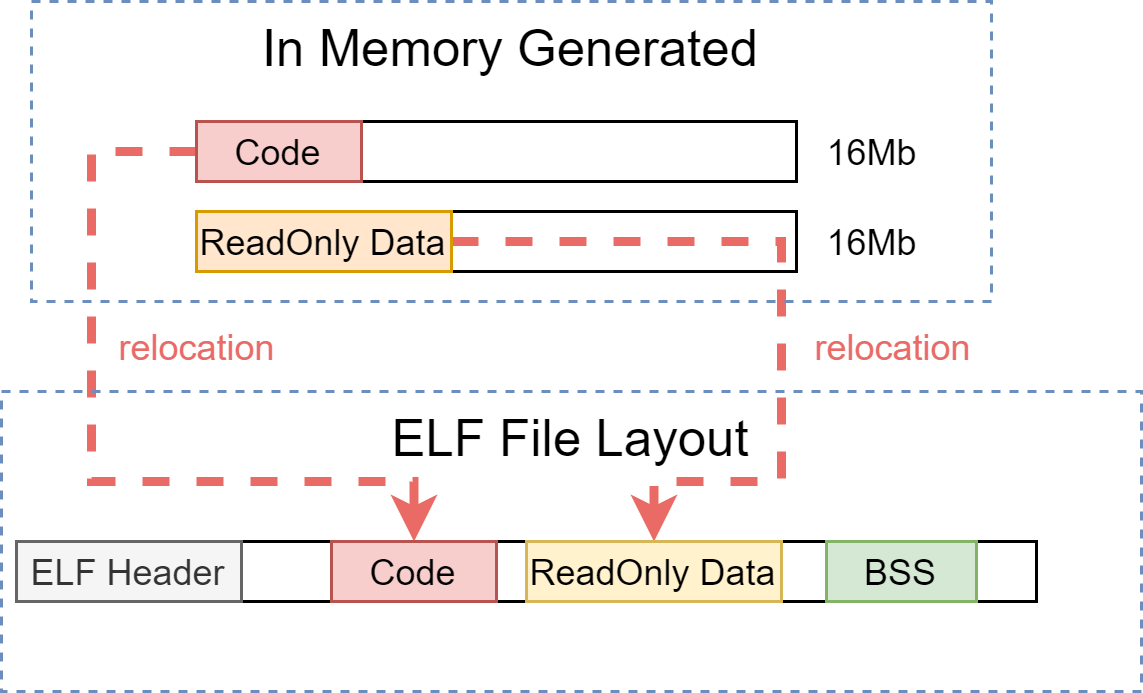

We are using our same virtual memory allocator also for storing generated code and data, but a block region of code has more reserved memory (e.g 16Mb) than it is actually using (committed). It means that the offsets between code and data at compilation time (in-memory) will be different once translated back to a file layout. This is the process of relocation:

Recall from the previous section about data layout that we need also to perform these relocations for data when a data is referencing another data (e.g the pointer to []u8 or the *Impl for type) or a pointer to a code (e.g the address of a native function stored in a const data - used by function pointers, vtable...).

Finally, the sections/segments in the final ELF file need to be also aligned so that the in-memory representation will be at the same offset than the file representation and has to be accounted when performing the final relocations of all symbols.

Challenges

There are many challenges ahead that I didn't have time to evaluate during this first year prototype:

- Handle of const generic literal types.

- Handle virtual calls with virtual tables.

- Handle interface calls: remember that unlike .NET, an interface in Stark is a fat pointer composed of an object target and a side vtable. It allows typically to declare an implementation of an interface for a type outside of a type, which is very powerful. It makes also function pointers calls a lot more faster (they are very costly in .NET).

- Handle function pointers (similar to interface calls).

- Generate debug info (even though my DWARF library is up and ready to be used!).

- Generate stack-walk frames and GC stack frames: these are both generated by RyuJIT via a callback when generating code. Stark will have to re-package these data, as we will likely use a different format.

- Support for SIMD intrinsics: Stark will provide similar access to SIMD types and hardware intrinsics. The difference will be mostly around functions and namespaces naming. It will likely require a change to RyuJIT, unless I can find a way to the RyuJIT integration by mocking Stark SIMD functions/types as .NET SIMD function/types. We will see!

Open-Sourcing

Unlike the Stark front-end compiler - along its runtime which is open-source at https://github.com/stark-lang/stark, the native compiler will remain closed source for now. It is mainly an opportunity for me to keep this project in a potential business-able state. But this blog post is giving you lots of insights about how it was developed - even though there are many tricks and the real challenge is to plug all of these together in the details, but at least, you can enjoy some overview of these details! ;)

But it is not completely closed-source either, as most of the code I have developed for this prototype has been made OSS:

And these are not small OSS libraries to develop!

Next Steps

Developing a native compiler bottom-up to the front-end compiler that can generate an actual executable was a fantastic and exciting achievement to see in motion when running the prototype with QEMU.

But the success of this enterprise is also largely due to the availability of RyuJIT and the feedback of the .NET ecosystem that helped to make this endeavor more practical for an individual.

The development of the prototype was always strongly focused on the target of developing a small Hello-World program around a seL4 micro-kernel, which helped me being concentrated - and motivated along the way. By the number of side-OSS projects that I had to develop to make this possible, you can imagine how much work it is to bring this to life!

Anyway, we still need to talk about the end of this first prototype through the integration with seL4 micro-kernel, and how Melody will be built around that.

Stay tuned for a next blog post.

Happy coding!