This is the first part of the blog post series about The Odyssey of Stark and Melody and more specifically, about the development of the syntax of the Stark language and its front-end compiler, based on a fork of the C# Roslyn compiler, during its first year prototype last year.

Overview

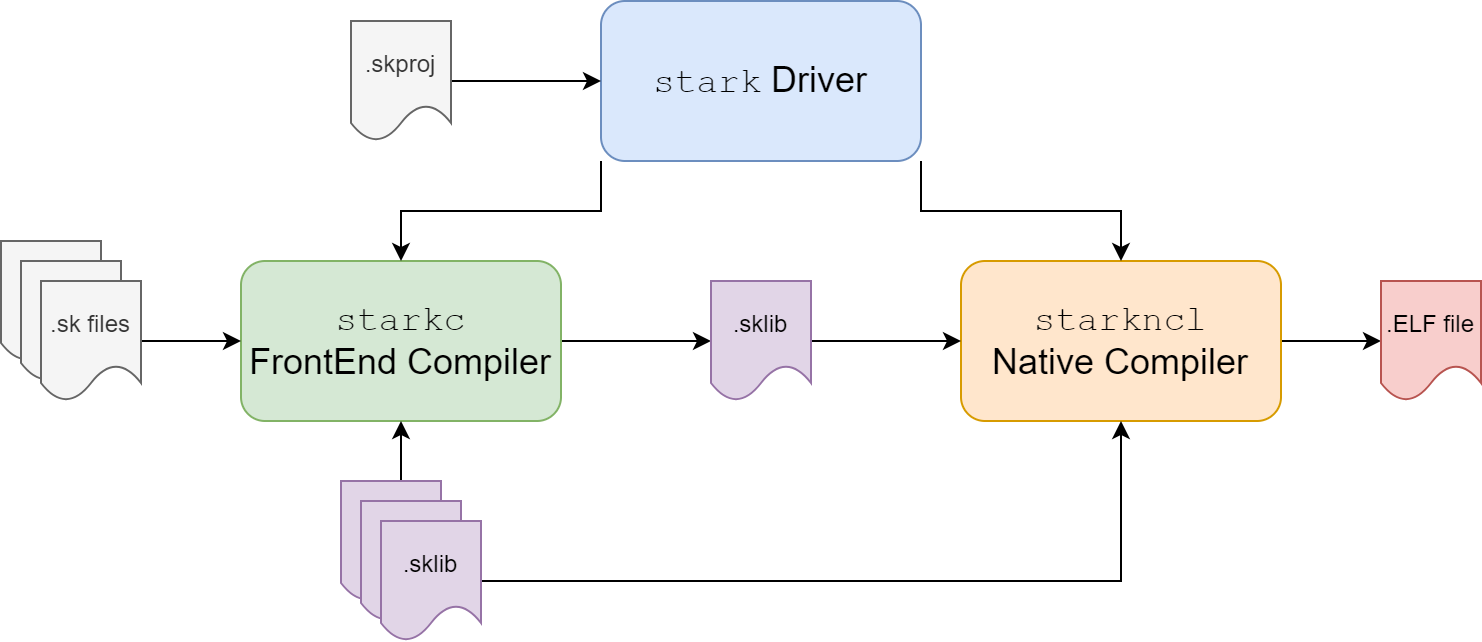

The role of a compiler is to transform a higher level representation of some code to a lower level representation, up to an ultimate representation into executable machine code.

This refinement doesn't have to be in one step (e.g source language to native code directly) and actually, it makes more sense to do it in several steps, because we can bring more - build and compile time - optimization opportunities along these steps, while it is also simplifying the domain problem on each refinement steps.

To that end, the .NET ecosystem is giving a good basis to work with: a .NET assembly is an intermediate binary representation of source code (following the well defined ECMA-335 specifications) and it brings several key features:

- Its format is compact and you can almost represent any code with it (e.g including C++ code).

- It contains both the interface of your code and the implementation, encoded in a binary format that stills keep track of high level types, method signatures, contracts...

- It doesn't enforce rules about inline-ability, all your code is there, you can decide later how you want to project it (debug vs release, -O2 vs -O3)

- It can contain compile time attributes that can be used by other post-processing tools or native compilers.

- There are multiple tools - OSS and commercial - to inspect them: ILSpy, dnSpy, dotPeek...

- There are .NET libraries to manipulate them: Mono.Cecil, System.Reflection.Metadata...

- It is a proven technology used by several existing compilers (e.g Roslyn for C#/VB, or F# compiler)

- It not only meant to transport a compact representation of your code but also an easier way for a native compiler to transform it to native code later, and to make better codegen decisions.

For Stark, I would like the entire build, compile, tests, benchmarks and package pipeline to be as much as stream-lined, integrated and efficient as possible, in order to provide a great development experience. The idea would be to have a stark driver command that is able to do all of this efficiently. For instance, unlike the .NET ecosystem that relies on msbuild, I would prefer this driver to leverage more potential build time optimizations - by using a persistent compiler driver/server for the full toolchain, including support for intellisense. So when today there is starkc command, ultimately, this command will be part of a larger compiler server that will integrate with package, native compilation...

Reusing the infrastructure provided by .NET assembly fits perfectly into this picture. The frontend compiler would be responsible to transform Stark language source code into sklib files (which would be similar to .NET assembly). Maybe later we can rethink of a more optimized format for storing its IR (optimized for faster codegen), but for now, it's already good enough.

Then, the obvious challenge is to transform source code to an sklib Library through a front-end compiler (the green part in the diagram above), but developing such a compiler for an individual is barely achievable. So instead of taking that long and uncertain route, and thanks again to the .NET ecosystem, we could leverage on an existing, strong (and complex!) compiler like Roslyn to kickstart this work.

I had already some good experience with Roslyn, but to my knowledge, nobody ever tried to reuse it to develop a completely new language with it for a different and new platform (or even an OS), so that was the goal of this first year: transform Roslyn to support a new language with a different syntax while keeping its "imperative" language class nature (meaning that we can't modify fundamentally how type inference is achieved for example).

So let's see how the Stark language has been prototyped during this first year with a fork of Roslyn.

Based on Roslyn

Changing Roslyn to create a new language is very challenging for several reasons:

- The codebase is huge, years of development, with 2 languages C# and VB.

- The repository is itself compiled with preview of Roslyn fetched from internal NuGet feeds.

- The projects have lots of dependencies over the VisualStudio SDK and again preview versions.

- Projects have lots of dependencies, one change in a core project might lead to change 1000+ references in the entire codebase.

- The codebase is evolving, new features, bug fixes coming upstream. Even if the public API doesn't change much, the internals can.

- Some design decisions made very early in the development of Roslyn are making changes a lot more laborious. Example:

- ref types are not represented by a proper type, so a ref kind has to be propagated all over the places along its associated type

- Nullable types are put in a thin struct wrapper around real types. They are also not a proper types in the system.

In order to make some progress for prototyping a new language, I had to cut lots of existing code and take hard decisions:

- I had to remove VB to avoid having to maintain the changes I was making on the C# and core parts of the compiler.

- I had to rename namespaces (e.g

CSharp=>Stark) - After a few months trying to keep the fork up-to-date with upstream, I made a hard fork

- Because I was also making changes to

System.Reflection.Metadatawhich was in the CoreFx repository, the sync was becoming impossible. - The hard fork allowed me to remove the internal NuGet feeds and complex build pipeline of Roslyn by using a regular .NET Standard 2.0 project without any custom NuGet packages.

- After trying to maintain Visual Studio Roslyn Integration, I also removed it: This was a tough decision, but this part is too difficult to keep-up with, and it brings a complexity that I couldn't maintain on my own. I decided that providing a good integration with

Visual Studio Codewould be much easier for the project in the medium term.

- Because I was also making changes to

- I removed all the existing tests: This was also too difficult to maintain while prototyping a new syntax. I decided that I would use during the beginning the runtime of stark as a "testing suite". For this reason, the runtime is maintained in the same repository under

src/runtimefolder- A change to the syntax is now sync with the change to the runtime. It makes iteration vastly easier.

- Tests will be re-introduced later once the syntax is a bit more stable. Nonetheless, that will be a huge work and some help will be much welcome!

The front-end compiler and runtime of Stark are hosted on https://github.com/stark-lang/stark

Leaner syntax

Most of the early changes concerned only LanguageParser.cs (the lexer/parser) in Roslyn codebase and it was the easiest place to start with and to see how difficult it would be to change the syntax.

As I discovered and explained in my previous posts about the Stark Language syntax, a lean syntax here might be appealing for some but not for others. It highly depends on your personal taste and experience with languages, how long have you been using some particular syntaxes, if you have been navigating between multiple languages and different paradigm (e.g functional vs imperative)... There is no such thing as "natural" programming syntax but there are lots of religion and way of thinking around existing programing languages. So by no surprise, Stark syntax is mostly colored by my personal relation with programing languages and by what I have seen during my career.

Typically, one of the very first change I made was to remove the need for semi-colon ; (as Swift Language did for example) but I have kept braces { and }, while I also removed the need for using parenthesis with control flows.

Originally for Stark, I had a plan to use space sensitive language (like python or F#), but realized that it would be too painful to retrofit in Roslyn and by the fact also that braces can allow compact syntaxes (specially with closures) that are difficult to express without.

Then I started to bring some more important syntax changes:

Use of

importkeyword instead ofusingto import namespacesIntroduction of modules like in F# (static class in C#) but they would work the same way with

import(no need to sayimport static)// Import namespace core import core // Import module core.runtime import core.runtime // Declare an empty module public module my_module { }The introduction of module as first class construction is important to make also functions first class.

Only one

namespaceper file, namespace would not require braces and should come first in the file. This is similar to Java for instance.namespace core public virtual class Object { private unsafe let _type : Type public constructor() { } }Use of the keyword

constructorfor declaring a constructor.Use of a simple naming convention derived from Rust:

- Using

UpperCamelCasefor "type-level" constructs (class, struct, enum, interface, union, extension) - And

snake_casefor "value-level" constructs - A departure from C# is that modules and namespaces are following

snake_case

Item Convention Package snake_case(but prefer single word)Namespace snake_case(but prefer single word)Module snake_case(but prefer single word)Types: class, struct, interface, enum, union UpperCamelCaseUnion cases UpperCamelCaseFunctions snake_caseLocal variables snake_caseStatic variables SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASEConstant variables SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASEEnum items SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASEType parameters concise UpperCamelCase, prefixed by single uppercase letter:T- Using

Use of a more uniform naming for primitive types, following the syntax of Rust:

C# Stark boolboolbyteu8sbytei8shorti16ushortu16inti32uintu32longi64ulongu64System.IntPtrintSystme.UIntPtruintfloatf32doublef64objectobjectstringstring

You will notice thatintanduintrepresents actually native integers (e.g anintis ani32ori64depending if the target CPU 32 or 64 bits). In Stark, they are first class types and are for example used as the default type for array/collection size/indexers.Use of

implementsinterface inheritance/prototype contracts andextendsfor sub-classing, similar to Java.namespace core public abstract class Array implements ISizeable {}namespace core import core.runtime /// Base class for an exception public abstract immutable class Exception extends Error { protected constructor() { } }Use of

virtualon class definition to specify that they can be sub-classed. They aresealed(in C# terminology) by default.Use of only one syntax for

forwhich would be equivalent of theforeachsyntax in C#public static func sun_range(range: Range) -> int { var result : int = 141 for x in range { result += x } return result }For iterating over an integer range (e.g

for(int i = 0; i < array.size; i++)) the equivalent in Stark is to use the Range syntax as a Range in Stark is iterable:public static func sun_range(array: []u8) -> int { var result : int = 0 for i in 0..<array.size { result += array[i] } return result }Mandatory braces

{and}for all control flowsLeft to right syntax, to simplify parsing and to make reading "left to right" matching what you are actually writing in the code (similar to Go lang):

- A function declaration is:

public func myfunction() {} - A variable declaration is

var x = 5 - A variable declaration with single assignment is

let y = "test" - An array of unsigned 8 bits is

[]u8 - An optional object

?object - An optional array of optional string is

?[]?string

- A function declaration is:

Make parameters declaration name first and then type, separated by a

:colon

public static func process_elements(array: []u8, offset: int, length: int) -> int {

// ...

}

- Casting between types is using the

assyntax:var a_float = 123 as f32 var an_int = 1.5 as int - Variable/field assignment:

varfor multiple assignments,letfor single assignment.var this_is_a_var = 123 let this_is_a_let = 124 this_is_a_var = 5 // this_is_a_let = 6 // Can't assign again for let - Add if/then/else expression instead of C# ternary

cond ? value_true : value_false:// if in an expression var result = if cond then 1 else 2 // If as a statement if cond then { // ... } else { // ... } - Attribute syntax is following the Java attributes prefixed by

@. You can still have multiple attributes but they don't need to be enclosed within brackets and separated by commas.@AttributeUsage(AttributeTargets.PARAMETER) @ThisIsAnotherWithoutParenthesis public class MyAttribute extends Attribute { public constructor() {} }

Remove boxing and object default methods

In Stark, boxing a value-type automatically to a managed object is no longer possible. You can't cast an int to an object, so you can't allocate accidentally on the heap.

The collateral effect of this change is also that you can't cast a struct to an interface even if that struct implements that interface. If you need to call a struct through an interface, it has to go through a generic constraint call.

Also consequently, all the default virtual methods inherited by all objects were removed from object class definition:

~object()destructorbool Equals(object)int GetHashCode()string ToString()

It should help to have a smaller footprint for runtime metadata for reference types. The VTable for objects in Stark would be empty by default.

An important benefit of these changes is that pointers can now be used as generic arguments:

var list = new List<*u8>() // declare a list of pointer to u8

(Because in regular ECMA-335, pointers are not inheriting from System.ValueType and so they cannot be boxed)

You may wonder why it is important to have that support: It can be useful if you are developing low level parts in a kernel OS where you don't have yet a GC running but you still want to use container classes to manipulate kernel objects and structures.

Arrays

First, array co-variance is one of the big legacy design decision that is now possible to revisit in Stark.

In C#, Arrays are co-variant, meaning that this is possible:

var array_of_string = new string[] { "a", "b" };

var array_of_object = (object[])array_of_string;

array_of_object[0] = 1; // will result in a runtime cast error

Not only it can be error prone but it has a cost at runtime, as an array write access can lead to perform a type cast check.

In Stark, arrays are no longer co-variant.

Note: This is not yet implemented in the front-end compiler but should not be much trouble to bring.

Also, any array like data are sharing the same base interface IArray<T>, that defines the minimal contract for an array: the size property, ref indexer and the assumption that the data are sequential in memory. The following types are all inheriting from IArray<T>

- Managed arrays (e.g

[]u8) - String

- Fixed arrays (e.g

fixed [4]u8) - Slices (e,g

~[]u8)

Strings

A String in Stark is UTF8 by default. It is even just a sequence of byte and the string type is actually a small struct wrapping this byte buffer:

namespace core

/// A string is a struct wrapping an array of u8

/// Can be mutable or immutable/readable and sharing

/// the same interface as arrays

public struct String implements IArray<u8> {

private let _buffer : []u8

public constructor(size: int)

requires size >= 0 {

_buffer = new [size]u8

}

public constructor(buffer: []u8) {

_buffer = buffer

}

// ...

}

This is very similar to what has been adopted for strings in GoLang.

The type char has been also replaced by the type rune which has the size of an i32 (unicode codepoint).

Fixed Arrays and generic literals

In C#, generic parameters are only meant to be Type definitions. You can't design something like SmallList<T, 5> where the implementation would store 5 consecutive T elements or overflow to a managed array if there is not enough room.

Generic literals are critical to introduce more efficient algorithms usually for performance reasons (e.g specialized codegen) and to improve locality (e.g fixed amount of co-located data).

In Stark, It is possible to add a generic parameter constraint to expect a const literal primitive (e.g const int). For example, a fixed array in Stark is declared like this:

namespace core

import core.runtime

public struct FixedArray<T, tSize> implements IArray<T> where tSize: is const int

{

// The array cannot be initialized by using directly this class

private constructor() {}

// size is readable

public func size -> int => tSize

// ...

}

It is then possible to use fixed array with the following syntax:

public class PlayFixedArray {

// Declare a field with a fixed size array

public var field_table: [4]int

// Fixed size array of objects

public var field_table_of_objects: [3]object

}

public module fixedarray_playground {

public static func play_with_fixed(cls: PlayFixedArray,

fixed_array_by_ref: ref [2]int) -> int {

// Fixed size array access

return cls.field_table[0] + fixed_array_by_ref[1]

}

}

Note: The syntax is not definitive, as it could conflict with normal array (e.g in case we want to allocate a managed array on the stack), it is more likely that fixed array will require a prefix e.g

fixed []u8or different syntax (but then more cryptic).

This type can then be reused in higher level containers (e.g SmallList<T, tSize>)

The FixedArray type is also a special case for the native compiler. As you can see above, the struct doesn't contain any field declarations, but the native compiler will generate them when the struct is being used.

At the IL level, I had to modify ECMA-335 to introduce a new generic type literal reference and also a new IL opcode to load its value. For instance the property public func size -> int => tSize which is returning the tSize generic argument is translated at the IL level to a new opcode ldtarg !tSize:

// Token: 0x06000035 RID: 53 RVA: 0x0000240B File Offset: 0x0000060B

.method public final hidebysig specialname newslot virtual

instance native int get_size () cil managed

{

// Header Size: 1 byte

// Code Size: 6 (0x6) bytes

.maxstack 8

/* 0x0000060C E11200001B */ IL_0000: ldtarg !tSize

/* 0x00000611 2A */ IL_0005: ret

} // end of method FixedArray`2::get_size

Though, there are still challenges ahead related to how far we will allow to create const literals from const expressions:

public struct HalfFixedArray<T, tSize> where tSize: is const int {

// Some challenge ahead to store this computation at IL level

public var field_table: [tSize / 2 + 1]T

}

Iterator

In .NET, the IEnumerable<T> provides a pattern to iterate on a sequence of elements and mostly relevant when used in conjunction with the foreach syntax. In Rethinking Enumerable Jared Parsons explained what is not working well with IEnumerable<T> and explored a different way of iterating on elements.

For the same reasons, Stark is departing from .NET IEnumerable<T> by introducing Iterable<T, TIterator>, where TIterator contains the state of the iteration:

namespace core

/// Base interface for iterable items

public interface Iterable<out T, TIterator>

{

/// Starts the iterator

readable func iterate_begin() -> TIterator

/// Returns true if the iterable has a current element

readable func iterate_has_current(iterator: ref TIterator) -> bool

/// Returns the current element

readable func iterate_current(iterator: ref TIterator) -> T

/// Moves the iterator to the next element

readable func iterate_next(iterator: ref TIterator)

/// Ends the iterator

readable func iterate_end(iterator: ref TIterator)

}

And it's usage in Stark is no different than in C# with foreach:

public static func sum(indices: List<int>) -> int {

var result : int = 0

for x in indices {

result += x

}

return result

}

In the case of List<int> the iterator state is simply an integer, the index of the element.

The generated code under the hood is doing something like this:

public static func sum(indices: List<int>) -> int {

var result : int = 0

var iterator = indices.iterate_begin()

while indices.iterate_has_current(ref iterator) {

var x = indices.iterate_current(ref iterator)

result += x

indices.iterate_next(ref iterator)

}

indices.iterate_end(ref iterator)

return result

}

The implementation for List<T> would inherit from Iterable<T, int> with the methods:

readable func Iterable<T, int>.iterate_begin() -> int => 0

readable func Iterable<T, int>.iterate_has_current(index: ref int) -> bool => index < size

readable func Iterable<T, int>.iterate_current(index: ref int) -> T => this[index]

readable func Iterable<T, int>.iterate_next(index: ref int) => index++

readable func Iterable<T, int>.iterate_end(state: ref int) {}

The major benefits of using such a pattern:

- The iterator state is separated and can be a value-type.

- The generated code doesn't box (in C# you would have to create duck typing GetEnumerator() method to workaround it).

- The implementation is simple and straightforward, no need for an extra-type (e.g the Enumerator). Many iterators on indexed containers can use the iterator state

int. - Implementing

Linqover this iterator should allow to generate efficient inlined code. - The

try/finallywould be triggered only if the iterator inherits fromIDisposable(not implemented in the current prototype). - It could also support mutable iterator (an mutable_iterate_current that return a ref)

Note that it is a first try at implementing differently an iterator. An objection to this design is the need to have 3 methods (

has_current,current,next) to implement something that could be implemented in a single method call:func iterable_next(iterator: ref TIterator) -> ?TThis single method approach makes it easier to decide in one go if it can continue and fetch the value at the same time. But it also complicates the iterator state implementation: For an array index, it would have to start at -1, and in next, would have to check

index + 1againstsize. The return value would also have to be returned for the end-of-iterator, a big structTeven if wrapped through an optional?Tcould still take precious CPU cycles for an empty iterator.So the design is still open to debate.

Range and Slice

Unlike in C#, Ranges in Stark are iterate-able and are supported by for loop iteration (foreach in C#). This helps also to remove the C for legacy loop construction.

A Range in stark is inclusive, so 0..1 would contain 0 and 1.

public static func sun_range() -> int {

var result : int = 0

// iterates from -1 to 1 inclusive

for x in -1..1 {

result += x

}

return result // returns 0

}

In order to iterate on an array by using its length, you can use the syntax 0..<array.size and it would create a range that is 0..(array.size-1):

public static func sun_range(array: []u8) -> int {

var result : int = 0

for i in 0..<array.size {

result += array[i]

}

return result

}

Note that there is a design flaw between Iterable and Range that makes it not possible to iterate from

int.min_value..int.max_value

Ranges are more useful for creating slices from existing data. In C#, when a range is used with an indexer on a string or an array, it will create a copy of the original data, with a hidden heap allocation.

Stark is introducing the struct Slice<TArray, T> where TArray is an IArray<T> that provides a view (and not a copy) around an existing struct/class implementing the IArray<T> interface. The syntax is using the prefix tilde ~. A slice of an array of u8 can be expressed as ~[]u8 that translates to Slice<[]u8, u8>:

/// return the slice "abcd"

public static func get_slice_with_string() -> ~string => "abcd"

/// return the slice "ab"

public static func get_slice_with_string_range() -> ~string => "abcd"[0..1]

/// return a slice of a slice from a slice

public static func get_slice_of_slice(slice: ~string) -> ~string => slice[0..2][0..1]

/// return a slice from an array

public static func get_slice_with_array(array: []int) -> ~[]int => array[0..1]

The error model

In order to differentiate non-recoverable programming errors from OS/user exceptions (e.g IO), the error model of Stark is following the feedback from Midori - The Error Model

- Aborts are non-recoverable errors that can be either:

- Generated errors by contract at compile time

- Runtime errors when it is not possible to detect this at compile time

- Explicit aborts via runtime asserts

- Checked exceptions for OS/user exceptions (e.g IO)

namespace core

import core.runtime

public interface IArray<T> extends ISizeable, MutableIterable<T, int> {

/// ref indexer #2, not readable

func operator [index: int] -> ref T

requires index >= 0 && index < size {

get

}

}

Note that while the parser is currently accepting this syntax, the work to fully support this has not been done yet

It will require to store the IL instructions for the

requiresclause, as well as having a simplified interpreter at compile time and fallback to a runtime error if not possible.

And for checked exceptions, the syntax is following the Java syntax:

// Valid (throws declared)

public static func throw_my_exception() throws MyException {

throw new MyException()

}

// Calling a method that throws without `try method()` is invalid

public static func call_a_method_which_throws_invalid() {

throw_my_exception() // generates a compiler error

}

// Valid (try with method throwing an exception)

public static func try_a_method_which_throws() throws Exception {

try throw_my_exception()

}

// Catching an exception does not require throws on method

public static func try_a_method_which_throws_but_is_caught() {

try {

try throw_my_exception()

} catch (MyException ex) {

// We don't rethrow

}

}

Exceptions need to be caught or declared on the method. Later Stark will also support try expression with Result<T> which will allow to perform pattern matching on it, to extract the exception or the result value of a method call.

Unsafe IL

Even if a language provides high-level constructs and safety, it requires often unrestricted access in order to provide safety (!) or more efficient code. These unsafe usages can still be abstracted and wrapped.

In C#, there is no easy support for that, so these days, you need to either:

- Use

System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafethough you can't do everything and it is bound to what is exposed - Use a solution like Fody coupled with InlineIL.Fody

In the F# code library, the F# compiler is allowing to inline IL with the syntax (# ... #) and it is used internally to unlock some low level parts that cannot be expressed in F#. In the past it was even allowed for user library, but I have read somewhere that it is no longer possible, which is fine in my opinion, as long as the language and runtime in the end are able to fill all the necessary missing gaps.

In the CoreRT compiler, they had to develop IL post processing (similar to Fody) to patch some methods like Unsafe utility methods.

In Stark, I have decided to bring back to life the old prototype Inline IL ASM in C# with Roslyn and improved its integration by allowing a new unsafe il syntax:

public func operator [index: int] -> ref T

requires index as uint < tSize as uint

{

get {

unsafe il {

ldarg.0

ldarg.1

sizeof T

conv.i

mul

add

ret

}

}

}

Others

During this first year, a few other areas were experimented or partially prototyped:

RuntimeExport/RuntimeImportsymbol binding: these are attributes that you can put on static methods providing dynamic weak static linking between low level parts in the language and their runtime projections:// In a first library A @RuntimeImport public extern static func allocate_object_heap(type: Type) -> object; // In a second library B that provides the implementation of allocate_object_heap @RuntimeExport("allocate_object_heap") public extern static func allocate_object_heap_x86(type: Type) -> object;Parameter less constructor for structs. In Stark, structs can declare a default constructor. This is especially important to support such a feature for correct support of safe object reference (no null)

public struct MyStruct { public constructor() { ... } }In addition to the existing attributes

CallerFilePath,CallerMemberName,CallerLineNumber, Stark provides a new compile time attributeCallerArgumentExpressionthat can extract a string representation of another argument for a method:// Declare the argument conditionAsText as a string representation of the argument condition public static func assert(condition: bool, @CallerArgumentExpression(nameof(condition)) conditionAsText: ?string = null ) { // ... } // implicitly conditionAsText = "this_is_an_expression && another_expression" assert(this_is_an_expression && another_expression)No

#ifdefbut config instead, similar to Rust[cfg]attribute!cfg. In Stark, I would like all the code variations shipped in the library that can be platform dependent or context dependent (tests, benchmarks) to be compiled into the same library.// Only valid when the "tests" config is passed to the native compiler @Config("tests") public module all_tests { @Test public static func my_test() { ... } }

But several areas have also not been yet prototyped during this first year:

- The introduction of isolated/readability/immutability concepts and compile time const data.

- Discriminated unions (struct and managed, also for

?TakaOption<T>) and associated pattern matching - Syntax for lifetime for heap allocation (e.g

new @PerRequest MyObject()or `new MyObject() in @PerRequest). - Extensions to add interfaces/methods/properties to an existing class/struct (e.g

public extension MyListExtension<T> with List<T> { ... }) - Lightweight function pointers: Unlike delegates in .NET, a function pointer in Stark would be struct, either static (one function pointer) or closure (one object reference + function pointer). The declaration would follow the declaration of a regular function

var action: static func(arg: int)is a static function pointer taking anintargument.var closure: func() -> intis a closure function taking no arguments but returning anint.

- Lightweight async/await

- Yield method iterators as value types.

- Stark driver using simple TOML config to build a library.

Departure from ECMA-335

A change like "remove boxing of value type" required a departure from ECMA-335 as a struct is identified at the IL level when it inherits System.ValueType which is a reference type. The following changes were applied to the standard:

In II.23.1.15 Flags for types [TypeAttributes] in the table, at the section Class semantics attributes:

| Flag | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

ClassSemanticsMask |

0x00000060 (changed) |

Use this mask to retrieve class semantics information. |

Class |

0x00000000 |

Type is a class |

Interface |

0x00000020 |

Type is an interface |

Struct |

0x00000040 (new) |

Type is a struct |

It's not the sole change that I had to make. For example:

- I have also added an

Alignmentfield toClassLayoutin order to specify custom alignment of types (e.g SIMD vector types can require 16 bytes or more) - And modified a couple of flags to (e.g

Intrinsicsattribute would translate to a flag on[MethodImplAttributes])

I'm trying to keep these changes documented in changes-to-ecma-335.md.

More changes will have to come for other language features:

requirescontract on methods- Checked exceptions

- Immutability/Readable/Isolated concepts

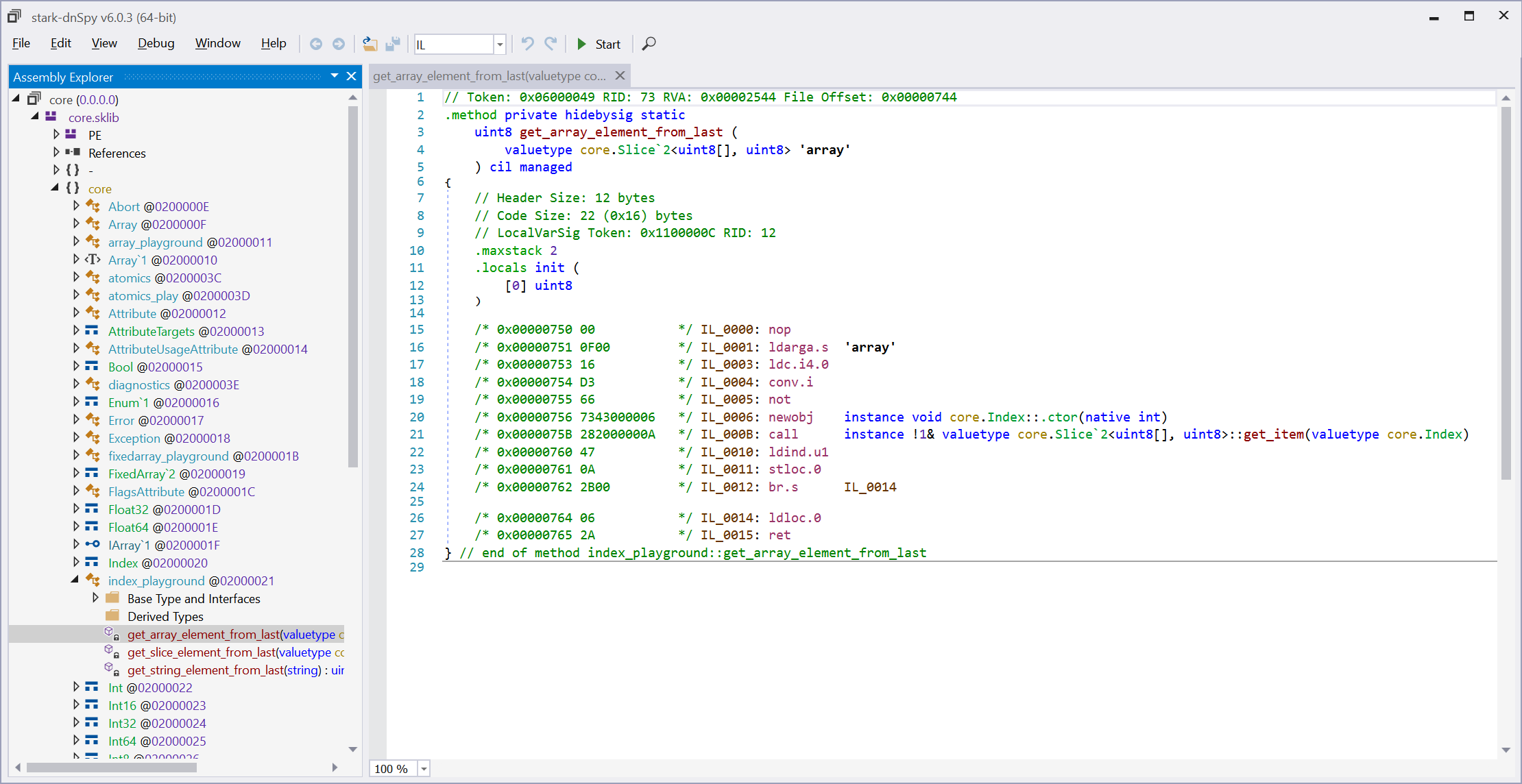

Fork of dnSpy

In order to check if the compiler was generating valid IL, I wanted to verify this with a tool like ILSpy or dnSpy. Because I had to make changes to ECMA-335/IL Format, I had also to make similar changes to an IL inspector.

I have been maintaining a fork of dnSpy for Stark:

I made the choice of dnSpy mostly because it was possible to inspect raw metadata as well.

Fork of System.Reflection.Metadata

Another consequence of the change to ECMA-335 is that I had to fork System.Reflection.Metadata which has been renamed to StarkPlatform.Reflection.Metadata.

This library is used by the Stark front-end compiler (e.g Roslyn for C#) to read and write assemblies but also by the native code compiler.

A few changes were made to the original library, like the support for UTF8 string storage and to allow to retrieve a UTF8 without having to allocate a manage object.

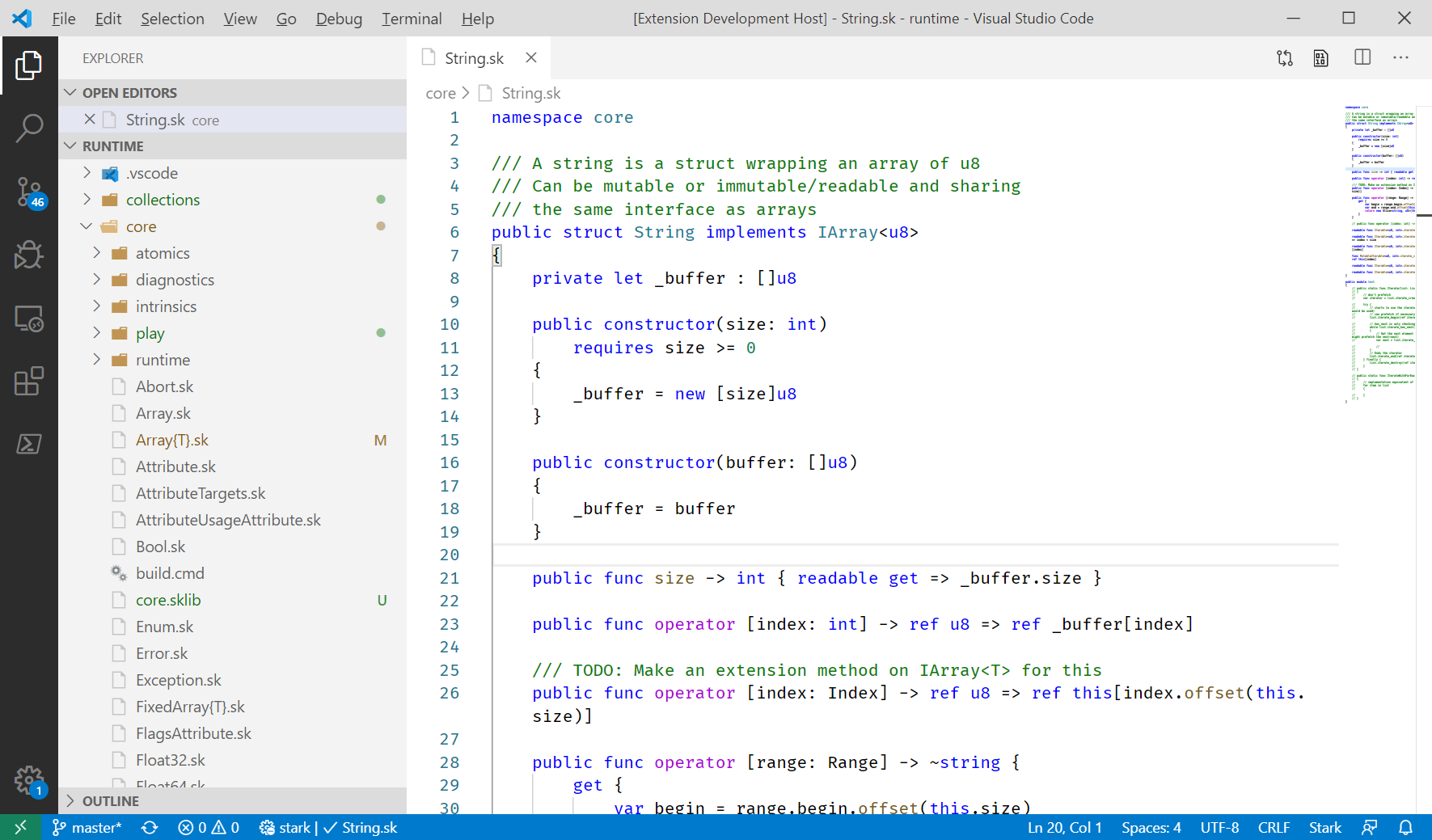

IDE Integration

I thought that I could re-use the integration of Roslyn with Visual Studio to provide an IDE integration but I couldn't get it working correctly. Roslyn is not a regular VS extension but is shipped within VS, and while I have done a few VS extensions in the past, it was way beyond my time and knowledge to be able to make it working.

So instead, I started to look at Visual Studio Code for at least a basic syntax highlighting experience and it turns out that VS Code is very easy to work with for that.

I developed a VS Code package with syntax highlighting for Stark by defining a simple TextMate definition file stark.YAML-tmLanguage. Because the syntax is in flux and it is very laborious to define the parsing through regex, I wrote syntax highlighting only for keywords (while for a language like C# they are defining the parsing of almost the entire grammar!).

I have also prototyped using Language Server Protocol just to see how complicated it would be to integrate with the more advanced user experience and it turns out that it is relatively easy to get notification on every single document change (see for example TextDocumentHandler)

Compiling the core library is done for now on the command line with a simple build.cmd but you can run also this command directly from VS Code and it will display clickable error messages.

So the current experience is very limited and rough, but it is enough to enjoy prototyping with it.

Not sure if I will be able to work on that any time soon, but enthusiastic contributors could help me developing that part! More on how to contribute in a following blog post.

Next Steps

This first year prototype helped to validate that it was possible to fork Roslyn to build an entire new language and start to build a new core library with it. While it is going to require lots of work to get it working entirely and correctly, it is very encouraging and promising!

The most challenging part of that work was to make changes to Roslyn, a huge and large codebase, without being able to get PR reviews from more knowledgeable folks of this codebase. I had sometimes to revert some changes realizing that it would not work. I know also that I will have some difficult changes to bring in the future and I fear them in advance.

Because I had to work on the native compiler part, I had also to stop working on the frontend for several months and getting back into the details after such a long period was quite difficult.

But this work on the frontend compiler was fundamental to allow the following work on the native compiler and it will be part of the next blog post of this blog post series!

Stay tuned and Happy coding!